The Last Word on Stablecoins and Free Banking

If you're going to compare the two, at least get the history right

If you ask a central banker about stablecoins, they will almost say something like the following:

“Stablecoins put private firms back in the business of issuing money. This was the status quo in the US before the Civil War, and it was an unstable, chaotic system, with banknotes trading at discounts to par, and wildcat banks running off with depositor cash and suffering from frequent runs.”

If they’re a little more sophisticated they might say something like “Stablecoins cannot serve as money because, just like wildcat-bank-issued banknotes, they violate the “no question asked” (NQA) principle. Users have to constantly underwrite the creditworthiness of each issuing institution, causing notes to trade at variable discounts to par. These frictions will prohibit such tokens from catching on in commerce.”

These comparisons – between stablecoins and the free banking era – actually predate even crypto. In 1996, Gerald Dwyer at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta wrote a paper called “Wildcat Banking, Banking Panics, and Free Banking in the United States” predicting that “electronic money is likely to consist of uninsured liabilities of private individuals or companies” – which is exactly what stablecoins were, pre-GENIUS. Dwyer thought that such electronic private monies would be issued in “less restrictive jurisdictions [which] could create a viable alternative even for transactions between U.S. residents,” aptly predicting the emergence of Tether two decades later. Even though the Atlanta Fed in its 1996 paper was sanguine about free banking, most central bankers today use free banks or “wildcats” as a stick to bash stablecoins with.

I first complained about this back in 2021, so rest assured, there are plenty of examples. But the comparison has reached a fever pitch with the passage of GENIUS. The negative association appears hardwired into central banker brains. Here are a few recent examples:

Hyun Song Shin of the BIS: “Stablecoin holdings are tagged with the name of the issuer, much like private banknotes circulating in the 19th century Free Banking era in the United States. As such, stablecoins often trade at varying exchange rates, undermining singleness. They are also unable to fulfil the no-questions-asked principle of bank-issued money”

Philip Lane of the ECB: “A change in sentiment about the capacity of the issuer to redeem the stablecoins at par could lead to systemic shocks and runs of the sort seen in the era of free banking, when private banks were given the authority to issue their own currency backed by Treasury bonds”

The economists at Biden’s treasury wrote in 2024: “In a similar manner to how privately-issued “wildcat” currencies were replaced by government-backed central currencies in the late-1800s, Central Bank Digital Currencies will likely need to replace stablecoins as the primary form of digital currency underpinning tokenized transactions”

And one of the most enduring aficionados of the stablecoin-wildcat bank comparison is of course Senator Elizabeth Warren. Here’s one typical example from a 2021 Senate Hearing:

As you rightly point out, this is not the first time that we've had private-sector alternatives to the dollar. In fact I'm going to go back further than you did. In the 19th century, ‘wildcat notes’ were issued by banks without any underlying assets. And eventually, the banks that issued these notes failed and public confidence in the banking system was undermined. The federal government stepped in, taxed these notes out of existence and developed a national currency instead. And that's why we've had the stability of a national currency.

These complaints are generally paired with the conclusion that CBDCs ought to replace stablecoins as a preferred form of digital money. Money is special, the thinking goes. Only a government can issue it credibly.

So foundational is this myth to western central banking that all evidence to the contrary is simply rejected. It’s perhaps not surprising then that when “free banking” (sometimes called laissez-faire banking) crops up, it is almost always done in a pejorative context. But when you consider the historical record, a few things become clear. Free banking, when genuinely free of government encumbrances, was remarkably successful, especially in Scotland and Canada. American “free” banking was a bit of a misnomer, and was hobbled by restrictions at the State level that made it unpredictable and chaotic. And crucially, when you consider today’s stablecoins against the failures of the banks in antebellum America, the specific reasons that free banks failed in the US are today addressed with stablecoins, especially in the post-GENIUS regime. In my view, the lessons of this particular historical episode actually vindicate the contemporary stablecoin project, rather than diminishing it.

What is free banking, anyway?

Larry White defines free banking as “the unrestricted competitive issue of specie‑convertible money by unprivileged banks.” Put more simply, it is a system in which banks could be created largely without restriction and freely issue notes with little or no government oversight. In classical free banking, banks would hold reserves of gold (specie, as in coins) and issue paper banknotes against those reserves. Crucially, the quantity of money was held in check by competitive market forces, rather than bank supervision or oversight. (Banks suspecting a peer of over-issuing notes against its reserves would launch strategic redemptions, draining the reserves of the problem bank. This market incentive kept banks from misbehaving.) Charter issuance was largely unrestricted. Free banking thus refers to decentralized, private-sector banking and note issuance. At its best it produced a stable and efficient monetary system in which a network of issuers distributed notes that generally traded at par and provided a suitable medium of exchange.

There exist well-documented instances of classical free banking in Scotland from 1716 to 1844, Canada from 1837 to 1914, in Sweden from the 1830s to the turn of the century. In all there are several dozen documented such episodes throughout history. In the thirty years preceding the Civil War in the US, there was an episode often referred to as “free banking,” in which the creation of non-chartered banks was freely permitted by many states. This was a bit more chaotic than the Scottish or Canadian experience. Even though the Scottish experience is very well documented, the American one is most commonly referred to today and is synonymous with free banking. This is ironic because in the US there were significant government-imposed constraints that impaired the effectiveness of the system.

It's important to situate free banking in context. The practice became possible in the 18th and 19th centuries due to a confluence of technological and institutional factors. Technologically, the emergence of high-quality banknote printing was a critical enabling factor. These were complex, intricate banknotes with watermarks, engravings, or vignettes that were costly to produce, but cheap to verify (sound familiar…?). But equally important, the world was very rapidly becoming a smaller place due to the emergence of railroads and telegraph networks, alongside reliable postal services. This meant that informational signals regarding private bank credibility were no longer bounded by geography. Banks could create clearinghouses and accept each other’s notes with confidence.

It’s worth noting that free banking was very much a disruptive phenomenon. The previous default was specie-based payments, as in making payments with literal silver and gold coins minted by the government. Alternatively, some governments issued paper banknotes, generally redeemable for precious metals, as far back as the 17th century in parts of Europe. These were government monopolies. In some cases, private money substitutes did emerge, like bills of exchange or promissory notes – effectively transferable private credit instruments used by merchants. So the notion of largely unregulated networks of banks issuing their own notes and having these private monies actually serve as the foundation for commerce was a pretty radical idea. It’s also worth noting that free banking only really took root in Anglo, Common Law countries. Civil law regimes found in France and the rest of continental Europe were more top-down in their approach to currency issuance and banking in general. Common law systems tend to be more localistic, flexible, and skeptical of centralized government power.

Politically, free banking in Scotland, Canada, and the U.S. emerged from governance voids. In 1707, Scotland officially became part of the United Kingdom, but retained legal independence and the ability to manage its banking system. The Bank of England had no monopoly on note issuance north of the border. Prior to confederation in 1867, Canada was a collection of British colonies with no monetary authority. The British did not set up a colonial central bank. The Bank of Montreal in 1817 was the first major bank and others followed suit. A robust free banking system followed and Canadian banks continued to privately issue banknotes until 1934. In the US, President Andrew Jackson destroyed the Second Bank of the United States in 1832, a quasi-central bank. The US government exited monetary policy altogether, leaving regulation to the states. In 1837, Michigan passed “free banking” laws and 17 states followed suit. These laws permitted entrepreneurs to start a bank if they deposited state bonds as collateral and allowed noteholders to redeem their notes for specie. Free banks compared with chartered banks, which could only be established by (hard to get) legislative charters. These charters were discretionary and the system was prone to favoritism. Free banks by contrast could be created by anyone as long as they satisfied the legal requirements. Jacksonian Democrats at the time viewed the chartered banks as tools of a privileged elite and saw the free banks as a rebellion against that status quo. Additionally, the US was undergoing extremely rapid westward expansion at the time, and more banking flexibility was needed on the frontier, which the free banks provided. Between 1837 and 1863, an estimated 872 free banks1 were established in 18 states. (This is Selgin’s estimate – many are higher).

To sum up, free banking became a phenomenon in certain legally flexible common law countries in the early 19th century which either maintained a political aversion to central banking, or simply didn’t have a strong monetary central authority in place. Communication technologies like railroads and the telegraph, combined with developments in note design, allowed notes to be credibly issued by a variety of private sector issuers and trade at par. Institutional developments like clearinghouses and countrywide branching facilitated mutual note acceptance and exchange, and allowed notes to trade at par and be used in commerce without merchants wondering about their value. Free banking largely ended when developed governments decided to move away from the gold standard (typically to finance wars) and began to see central banking as a critical tool to fund a modern, centralized state. It doesn’t exist today, because almost all governments exercise monetary sovereignty, and the issuance of money is seen as too important to be left to the private sector – not to mention that the world has been on an exclusively fiat standard since 1971. The notion of a bank holding physical gold in its vaults redeemable on demand is seen as quaint today.

Why were Scotland and Canada successful?

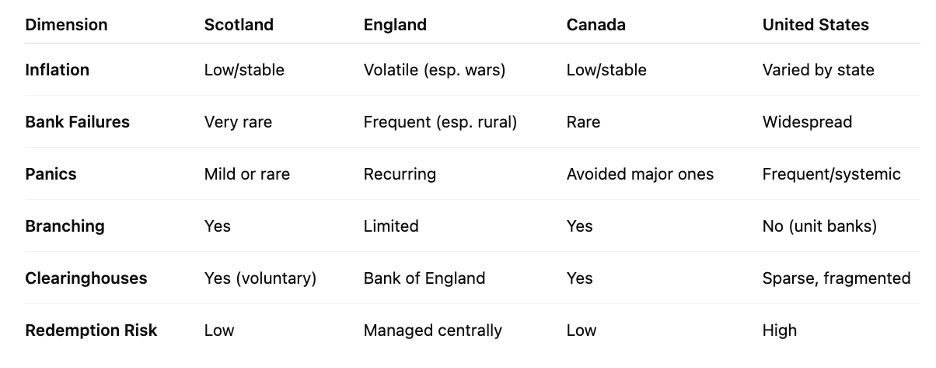

To understand why the US instance of “free banking” is a poor example to judge the concept by, we have to look first at the successful cases of Scotland and Canada. Both instances are particularly useful because during the same period, you had central banking in England, and quasi-free banking leading to the federalized National Banking System in the US. Because England and the US were macroeconomically similar enough to Scotland and Canada, respectively, we have great test cases for centralized versus free or decentralized banking systems. And boy did the free banking systems outperform.

If you compare England and Scotland during Scotland’s free banking era (1716 – 1845), Scotland had very low inflation, extremely infrequent bank failures (only one major bank, the Ayr Bank failed), and few and mild bank panics. England by contrast (which had a centrally managed banking system dominated by the Bank of England) had 300-400 documented bank failures, mostly clustered in crisis years (1772, 1793, 1810, 1825, 1847), and notably suspended gold convertibility between 1797 and 1821, although this was attributable to the Napoleonic wars.

During Canada’s free banking heyday (1817-1890), Canadian inflation was sub 1% or often deflationary, even during periods of economic expansion. Canada only suffered 12 chartered bank failures with half of those causing losses to depositors. Notably, in the failure of the Quebecois Banque Du Peuple in 1895, note holders were paid back in full due to a policy of director and shareholder unlimited liability. This meant that shareholders in the bank were personally liable for the bank’s debts. This caused ruin among many prominent French-Canadian elites who were shareholders in the bank. (This policy of unlimited liability was the custom in Scotland as well, and when the Ayr bank collapsed in 1772, many landed gentry who were shareholders in the bank were ruined.)

By contrast, during the same period, the US experienced hundreds of bank failures. Selgin estimates that of the roughly 1000 free banks that existed during the period, 242 failed, with other estimates being more aggressive. Failure rates for free banks are generally assessed in the 50 to 60 percent range. The US had numerous banking panics over the period: in 1819, 1837, 1857, 1873, 1893, and 1907. Canada experienced no systemic banking crises during the period and did not suspend specie redemption until the first world war.

So the respective track records clearly evidence that “true” free banking systems could dramatically outperform centrally managed ones when you consider the Scotland/England and Canada/US pairs. But how were the Scottish and Canadian systems actually run?

In Scotland, banks could be created by charter or as joint-stock companies. Most banks operated with unlimited shareholder liability. They issued their own banknotes which were redeemable for specie (during mature periods of free banking, banks only held 2-3% of liabilities in specie, as the banks were so trusted that notes were considered sufficiently credible. Redemption was possible but rarely done). There were no legal tender laws privileging any bank’s notes over another. Banks were discouraged from over-issuing notes through competitive market mechanisms, at first through note dueling and later through adverse clearing. Krozsner describes2 redemptive “note dueling” as an important stabilizing mechanism during the earlier stages of Scottish free banking:

The Royal Bank of Scotland, for example, would attempt to gather up as much of the outstanding note issue as possible from its rival, the Bank of Scotland. The bank hired people called “note pickers” to collect the rival’s notes, some of whom might even offer a little reward to individuals who would exchange their Bank of Scotland notes for the Royal Bank’s notes. The note pickers would then simultaneously converge upon the Bank of Scotland and demand: “redeem these notes as you promised, give us the gold now.” Because of this market mechanism – which could be thought of as runs on a bank – these banks, which were moving toward a fractional reserve system, could not reduce their reserves by too much (because of the threat of a redemption attack by their rivals). This mechanism was used by both large and small banks. Competitive rivalry thus had the salubrious effect of forcing rivals to maintain reasonable reserve ratios. And this important aspect of market discipline emerged naturally.

The Ayr bank was the one notorious exception to the tendency of Scottish banks not to over-issue. Aside from that, there were remarkably no major collapses in over 100 years of Scottish free banking.

In addition to competitive redemption, Scottish banks in 1770 developed a private note exchange and clearing system. This developed naturally with no government encouragement. Initially, banks were leery of accepting each others’ notes, as they did not want to promote competitors’ liquidity. But bank customers found this inconvenient and eventually the major banks in Edinburgh (the Bank of Scotland, the Linen Bank, and the Royal Bank3) started clearing trilaterally. They eventually brought the provincial banks into their system. Clients could deposit notes from one bank at its competitor and the banks would net out the balances once a week. This vastly increased the utility and credibility of the banknotes issued by the smaller, less trusted banks. You might wonder why the larger banks would patronize a system that helped their competitors. The reason was that it was profitable for all involved. Notes were non-interest bearing, and banks preferred to have notes in circulation as long as possible rather than redeemed. Central clearing allowed notes to stay in circulation longer.

Once clearing was established, a more systematic form of note dueling became possible. Banks that were suspected of over-issuing or solvency issues were subject to “adverse clearings,” whereby their peers could redeem large quantities of notes, draining their reserves and forcing them to reduce their note issue. Aside from the Ayr bank, the threat of adverse clearings kept the banks in check during the period, as Krozsner relates:

In order to get into the note exchange, a bank would have to be reputable. The clearinghouse did not set up explicit liquidity requirements or explicit capital requirements. And there were no government requirements on these matters. Members simply had to be able to meet the regular netting payments by the end of the week. Adverse clearings would signal to the other members that something may be wrong, and exclusion from the system was possible. The clearing system thus turned into a system of prudential private regulation because being in the note exchange system was sending a clear signal to the public that if these other banks, who best knew what was going on within the bank, are willing to accept these notes, then an ordinary person might be willing to accept them also.

Thanks to competitive pressures established by note dueling and clearing, Scottish banknotes traded at par and were accepted universally throughout Scotland during the period. Branching was also widespread. Interestingly, a similar clearing system (the Suffolk System) was established in New England during American free banking which mirrored the Scottish equivalents in Edinburgh and Glasgow. New England banks had to maintain balances at Suffolk Bank in Boston and agree to redeem notes at par. Suffolk could also redeem notes on behalf of the banks. Overissuing banks would have their balances drained via adverse clearings. While the Free Banking era in the US was often chaotic, the clearinghouse established in Boston kept the system orderly and kept notes trading at par throughout New England.

Canada offers a similar success story. Though the banking system wasn’t quite as “free” as it was in Scotland, and banks had to be chartered, these charters were widely available. Even though Canada was sparsely populated and governed a gigantic territory, branch networks were widespread enabling banks to obtain geographic diversification. Clearinghouses were established in major cities, but were less important in the Canadian system.

To summarize, both Scotland and Canada had extensive branch networks as well as influential clearinghouses (the US had only one major regional clearinghouse). Banks could diversify cross-regionally. Both Scotland and Canada had many fewer banks than the US during free banking (dozens rather than well over a thousand). In Scotland, no collateral at all was required for entry into banking, whereas in the US banks had to hold state bonds. And the results were very clear. Scotland and Canada dramatically outperformed England and the US on virtually all metrics of financial stability.

Why was US free banking considered a failure?

The critics of free banking in the US point out that notes issued by the free banks sometimes traded at discounts to par, especially if those notes were circulating far from the issuing bank, or the issuer was in financial distress. They also note the relatively high rates of bank failures and financial crises during the period. And on these points they are correct. However they conveniently elide the reasons that US free banking was less successful than its counterparts in Scotland or Canada, generally characterizing free banking itself as the culprit. Rarely do they consider the idiosyncratic regulatory reasons that are actually responsible for the failures of the system.

First it must be noted that free banking was adopted only by a subset of states at the time, and within that set, the outcomes varied widely. As George Selgin points out, only 18 of 34 states passed free banking laws. Throughout the period, the majority of banks in the US remained ordinary chartered banks. As Selgin relates, “In all, of some 2,450 state banks established between 1790 and the start of the passage of the National Currency Act in 1863, only 872, or a little over a third, were even nominally “free.”” And only a small subset of free banks was considered “wildcats.” These wildcats were banks which were fraudulent or created to be deliberately insolvent4, aiming only to take deposits and print notes, with no intention of standing up a legitimate business. The historian Hugh Rockoff defined a wildcat as a bank that “knowingly issued more notes than it planned to redeem, and that closed in a few months.”5 The story goes that bank branches were sometimes located in remote areas (“where the wildcats roam”), making redemption deliberately tricky. Of the 872 free banks, Selgin estimates that somewhere between “several dozen” and 173 could conceivably be called “wildcats”. Moreover, the wildcats were really only a feature of a few states – Michigan, Minnesota, Indiana, Wisconsin, and Illinois. In the literature, bank failures (which happened for a variety of exogenous reasons) are often conflated with wildcatting. In their review, the Atlanta Fed actually rebukes this claim:

There also is little evidence supporting a generalization that these free banks [in Indiana, Illinois, or Wisconsin] were imprudent, let alone financially reckless. The episodic difficulties faced by free banks were not self-induced implosions. In these instances, banks’ losses occurred sporadically when developments outside the banking systems decreased the demand for the banks’ notes or decreased the value of the banks’ assets.

The Minneapolis Fed in a 1982 report concurs:

The conventional view of this period is that wildcat bankers were roaming the countryside taking advantage of an unsuspecting public by issuing bank notes they had no intention of redeeming. By locating redemption offices in remote areas and absconding with their bank's assets, wildcat bankers supposedly made a hefty profit. We have no doubt that such bankers existed. A close look at the data from four free banking states, however, shows that a much better explanation of free banking's problems is that they were caused by capital losses that banks suffered when market forces drastically pushed down the prices of state bonds, a significant part of all free bank portfolios.6

As we will see, there were several reasons these banks were particularly vulnerable to external shocks. The free banks were not “free” in the sense that more unrestricted banking systems were, and this was the ultimate cause of the issues banks had in the US during the period. While US free banks were “free” in the sense that they could be founded without relying on the (generally corrupt, political favoritism-based) charter system, they were not free like Scottish banks were free. Crucially, all free banks in the US were “unit banks”, meaning that they were forbidden from opening multiple branches. By contrast, free banks in Scotland and Canada were not prohibited from branching (not required to hold government collateral), and were able to obtain geographic diversification.

Multiple branches meant banks were not as exposed to a failed harvest or a local recession in a single town or county. Branches also meant that redemption was more convenient, and so noteholders tended to trust banks more.

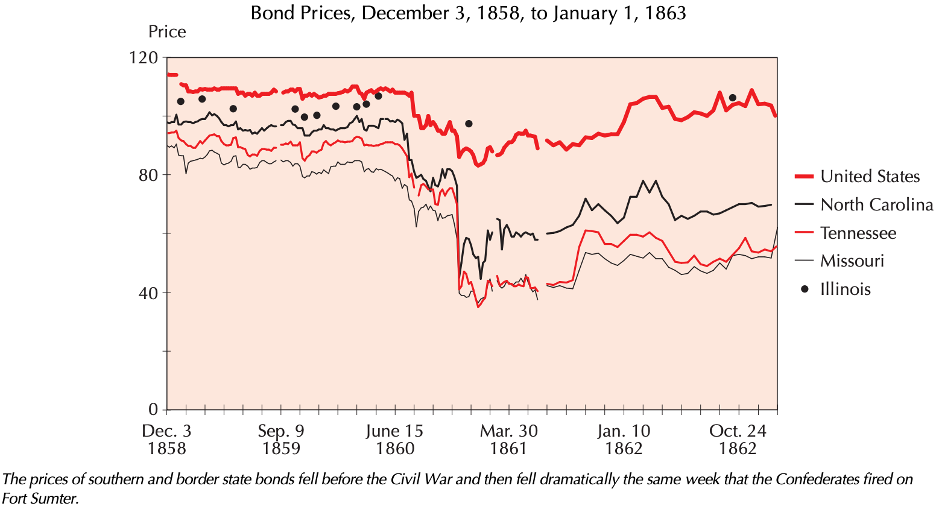

Additionally, depending on the state, free banks often had to post collateral in the form of state bonds in order to open. Many of these bonds were of a low quality or went to 0, causing the failures of some of the free banks. (Recall that we are situated in the pre-Civil War era, and many southern or border state bonds depreciated rapidly as secession became a possibility and then a reality.)

The lack of branching also made it difficult for banks to familiarize themselves with each other and build deeper relationships, which was a requirement for clearinghouses to emerge. These clearinghouses led to vastly more efficient banking practices and enabled notes to trade at par. (In places where clearinghouses did emerge in the US like the Suffolk System in New England, notes traded at par and the banking system was stable.)

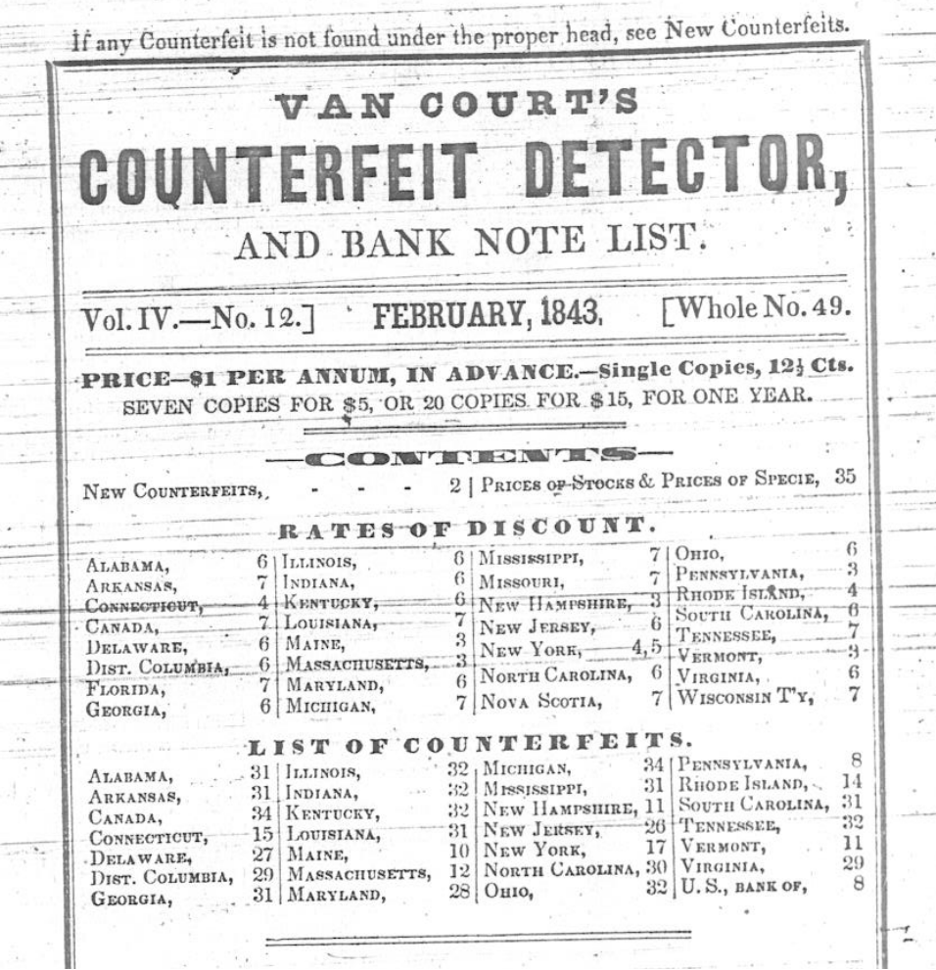

In the US, the general lack of central clearing and the existence of over a thousand highly localized unit banks meant that the further a note traveled from its point of origin, the less trusted it was in commerce. While notes often traded at par in their home markets, as Selgin notes, they often traded at discounts further afield. These reflected “the cost of sorting and returning them to their sources for payment in specie, plus that of bringing the specie home.” A number of publications emerged, like Van Court’s Bank Note Reporter in Philadelphia and Thompson’s Bank Note Reporter in New York, covering discount rates, counterfeit alerts, and bank reliability ratings for hundreds of banks.

Interestingly, the economist Gary Gorton (who has since become a rather fierce critic of stablecoins (via free banking) on the NQA basis) compiled some helpful data from Van Court’s Bank Note Reporter, revealing huge variation in the discounts applied to the states’ free bank notes. According to the data, notes from banks in Tennessee, Ohio, Nebraska, Mississippi, Michigan, Illinois, and Indiana generally traded at huge, double-digit discounts in Philadelphia, while other states’ notes generally were accepted at low single digit discounts. (For instance, between 1844 and 1851, notes from banks in Mississippi on average traded at discounts between 55 and 75 percent in Philadelphia. By contrast, notes from banks in Massachusetts (where the Suffolk System clearinghouse kept things remarkably stable) were commonly accepted in Philadelphia at discounts in the 25 basis point to two percent range.

Free banking critics like to exaggerate the influence of the wildcat banks on the note discounts. According to Selgin, merchants would simply refuse to accept notes from banks who were suspected of being insolvent, and note brokers would instead purchase these notes for their liquidation value (think of the brokers buying FTX claims). For the “bankable” yet discounted notes, the discounts reflected the (very real) cost of redemption for specie.

The data from Gorton points to a fundamental reality of the purported free banking system in the US: far from being one homogenous system, it was actually a patchwork of different state regulatory regimes. And indeed, the system was not “unregulated”, “laissez-faire”, or “free”, but rather harshly regulated by the states. By prohibiting unit banking, and stuffing the banks full of sometimes illiquid or depreciating state bonds, the banks were doomed to a state of fragility. Selgin shares one interesting example from Illinois demonstrating the pitfalls of the collateral requirements:

The hitch was that, of those $12 million in bonds [backing the Illinois free banks], over $9.5 million were from states that eventually joined the Confederacy. Illinois’s free banks thus suffered the same fate as Wisconsin’s: as the threat of secession grew, the backing for their notes shrank. On the eve of the Battle of Fort Sumter, most Southern-state bonds were worth about half their par value. Within a year, 90 banks closed their doors; and this time holders of their notes lost millions.

Dwyer’s data bears this out too. State bonds (which many free banks were forced to hold) sold off dramatically in the lead up to the Civil War. This doomed many banks holding the bonds. The Civil War marked the end of the free banking era in the US.

To summarize, the insistence by the states that banks not branch and hold (troubled) state banknotes created a state of fragility that led to numerous failures and waves of panics. The less regulated systems in Canada and Scotland where branching was ubiquitous, and collateral requirements were not as onerous, simply did not exhibit these issues.

One abiding question in my mind was why the states in the antebellum system in the US were so adamantly opposed to branching. As far as I can tell, this was rooted in the Jacksonian populism that abounded at the time. There was a deep fear of “financial elites” and moneyed interests, and a desire to support local banks and economies. Prohibiting branching was a way to stop the perceived incursion into local communities from the “big banks” out east in the large urban centers. But it was the aversion to branching more than any other factor that doomed the free banking system in the US. Had branching been permitted, clearinghouses like the Suffolk System that stabilized New England banking might have become ubiquitous in the US. At the time, due to branching, Canada managed to achieve mutual convertibility at par despite enormous geographic distances and sparse population, so it’s not out of the question the US could have done so as well.

Are stablecoins like free banks?

What are stablecoins? Thankfully today we are in the position to distinguish pre-GENIUS and post-GENIUS stablecoins. Before GENIUS we had Terra/Luna, Maker, algostables, crypto-backed stables, and all sorts of assorted nonsense. It was hard to reason about stablecoins because they weren’t homogenous entities. But because GENIUS is now the law of the land, and the bill makes my argument considerably stronger, I’m going to limit my comments to GENIUS-regulated stablecoins. So what is a federally-chartered stablecoin in year 1 AG (After GENIUS)?

Nationally-chartered stablecoins under GENIUS have the following characteristics:

They are federally regulated by the OCC

Issuers must back liability in full with reserves in liquid assets (cash, 90-day US Treasurys, reserves at the Fed)

Token holders have priority in bankruptcy or liquidation with a direct claim to the underlying assets

Issuers are required to honor same-day redemption at par

Issuers must produce monthly disclosures and quarterly financial audits

Issuers are effectively money warehouses, with no lending out of customer cash

Free banks, on the other hand, were lenders issuing notes redeemable for specie. The banks held a wide variety of assets on their balance sheets, including specie (often 10-20% of their liabilities), real estate, agricultural, or merchant loans, and other securities. Lending was the primary business model. Additionally, these free banks had to hold state or government securities as collateral to issue notes, but these weren’t held on the balance sheet and couldn’t be used for liquidity. These banks, being undiversified unit banks, were very much exposed to the particular (often agricultural) communities they lent to. One failed harvest and they could be in trouble.

So the nature of the asset portfolio and the fundamental business model are wildly different. Banks held all sorts of assets of varying durations and were naturally exposed to runs. Stablecoins hold either cash or short-dated Treasurys, the most liquid and reliable securities on the planet. Stablecoins are much more comparable to money market mutual funds, and even within that cohort, they are on the more secure side. While some MMMFs have “broken the buck” (traded below par), with the Reserve Fund infamously trading at a discount due to its holdings of Lehman commercial paper, no money market fund which holds exclusively short duration US Treasurys has ever suffered such a fate. For a GENIUS-compliant stablecoin issuer to somehow collapse, you’d need the US Treasury market to completely seize up. If this happens, the world is ending, and stablecoins are the least of our problems.

On the regulatory front, major stablecoins (with more than $10b in capitalization) are federally regulated, so this is another disanalogy to free banking. Before GENIUS, the stablecoin sector was a bit more analogous, as private sector issuers took in all kinds of assets and issued under a variety of regimes, some offshore, some lightly state-regulated, some more seriously state-regulated. You had crypto asset-backed stablecoins like Maker/Dai, synthetic, derivative-based dollars like Ethena, or largely unregulated issuers like Tether with a variety of backing assets. So you could say this was a bit similar to free banking, hence the numerous comparisons. Post-GENIUS, this has all been homogenized.

On the chartering front, free banks were notable in that they were generally open-entry, although chartering systems varied (in certain US states, charters were not required, in Scotland they were, but they were freely granted rather than discretionary, with Canada being the stingiest with charters). Under American free banking, any founder who was able to meet the legal requirements could start a free bank. Stablecoins under GENIUS by contrast are much more regulated; over the $10b threshold (de facto a bare minimum for a stablecoin issuer to be profitable and cover its fixed costs, especially as rates fall), OCC charters are required.

Why the pitfalls of American free banking showcase the value of stablecoins

As we’ve discussed, American free banking was unstable for a few key reasons:

Most banks were unit banks and were prohibited from branching. This meant that they could not achieve geographic diversification, redemption was expensive, and so was information. This manifested in discounts to par for notes that circulated great distances from their issuers.

Lack of clearinghouses. With some exceptions, like the Suffolk System, the unit banks that composed the free banking system in the US were not able to organize themselves into clearinghouses which were a precondition for widespread par acceptance of banknotes. These clearinghouses also served as a market mechanism to detect and punish over-issuance (through adverse clearings).

Notes traded at discounts due to the cost of redemption. Merchants were sometimes leery of accepting notes from distant banks, given the high cost of physically redeeming the banknote (due to a lack of branching), and also returning the specie. The lack of clearinghouses exacerbated this. Merchants had to consult publications to determine the appropriate discount, based on their city and the reputation of the issuing bank. These created unacceptable information costs that interfered with commerce.

Depending on the state, banks were forced to hold state bonds. Banks had to hold state bonds which were occasionally illiquid or depreciated quickly. Notably, in the prelude to the Civil War, state bonds associated with many Confederate states sold off rapidly, dooming free banks that held them as collateral.

In certain states, deliberately fraudulent ‘wildcat’ banks were the norm. Some banks were set up to issue notes and skip town, leading to the reputation of the free banking era as rife with fraud. These relatively isolated incidents are sometimes erroneously blamed for the high failure rate of free banks, which was more structural in nature.

If you consider the market for stablecoins, these concerns are either not present due to new technological modalities, or addressed by GENIUS.

Lack of “branching”: this is clearly not a problem with stablecoins. Stablecoins are natively global. Tether is traded against virtually every currency on the planet, on both major centralized exchanges as well as informal p2p exchanges. While redemption is generally limited to larger entities, most users do not interact directly with the issuers, but rather buy and sell stablecoins on the liquid secondary market.

Lack of clearinghouses: in the context of stablecoins, a clearinghouse would be a venue in which stablecoin issuers settle net obligations with each other, monitors member stablecoins for risk, and potentially penalize issuers with

notestokens trading below par. A clearinghouse could even potentially engage in risk mutualization or provide “stablecoin repo” to smooth liquidity when crypto markets have mismatches with banking hours. Such an entity doesn’t exist, but in practice these functions are performed by a robust and deep network of centralized and decentralized exchanges and third party liquidity providers. There is a huge market incentive to sniff out stress, illiquidity or insolvency in stablecoin issuers (to be expressed by short positions), and to do the converse (as was the case with funds longing USDC at 88c in March 2023). There are plenty of market makers and proprietary funds that maintain stablecoin pegs via arbitrage. For instance if Tether trades above par, a market maker is incentivized to create new units of USDT with cash and sell them at the market price – and vice versa. And of course there are highly liquid bespoke DeFi protocols where stablecoins trade against each other, with significant market incentives to surface and express any kind of underlying deficiency with a stablecoin issuer.Discounts due to redemption costs: technically, Tether does have a redemption and creation cost of 10 bps, but in practice these are not expressed in the price of USDT (as they commonly were for free bank banknotes). Circle generally has no fees for redemption or creation, although they have recently instituted tiered fees for frequent, larger redemptions. In practice, the highly liquid secondary markets for USDT and USDC in which the stablecoins generally trade at par or extremely close to it tend to outweigh the primary redemption markets. Discounts for stablecoins have been observed during periods of market stress (infamously with USDC during the SVB collapse in 2023), but post-GENIUS, no regulated stablecoin may hold large uninsured cash deposits, which was what got USDC into trouble.

Banks forced to hold inferior collateral: under GENIUS, stablecoins are mandated to hold only the highest and most liquid forms of reserves – either cash or short dated government debt. Of course, there are historical examples of stablecoins that held inferior reserves (with the horrifying Terra/Luna being backed by its own pseudoequity), but these alternative reserve structures are prohibited under GENIUS. Concerns about stablecoin reserves basically evaporated with GENIUS. It’s possible in the future that some kind of unanticipated crisis occurs wherein Treasury market liquidity seizes up, but it’s genuinely quite hard to envision a situation in which stablecoins get into trouble via their portfolios of short-dated USTs.

Fraudulent “wildcat” banks: deliberate fraud is always possible and no regulatory effort is sufficient to stamp it out entirely, but it would be extremely difficult for a GENIUS-regulated stablecoin to engage in deception. They have to submit highly granular data to their regulators, monthly attestations, and subject themselves to quarterly audits. Offshore, unregulated stablecoins, as we saw with Terra/Luna, remain buyer-beware territory. Under the more strict (Rockoffian) definition of a “wildcat”, a wildcat stablecoin would be an issuer that issues unbacked liabilities with the specific intent of not redeeming them for the underlying collateral. Perhaps Terra’s UST would fall under that definition, but determining Do Kwon’s intent is tricky. Maybe he genuinely thought the system could work with endogenous collateral. There is not much parallel in contemporary stablecoins for intentional wildcats.

What can we learn about stablecoins from free banking?

My intent with this piece is not to discourage anyone looking to financial history to make sense of things in the present day. Even though the political, technological, and legal contexts are vastly different between 18th century pre-industrial Scotland and present-day America, there are still lessons to be learned from free banking. Certainly, the stablecoin/free banking comparison appears apt on many levels. In both cases, you have a novel regulatory model for financial institutions issuing non-interest-bearing liabilities against some assets held in reserve. In both cases you have a history of notorious frauds and fly-by-night operators. Both free banking and stablecoins emerged to fill a void in a relatively new financial and political context. You have a decentralized network of issuers held in check by market mechanisms, not government. In both cases the liabilities sometimes traded at discounts, reflecting solvency and liquidity risk as well as the cost of redemption. In fact, I was so taken with the comparison that I made it the focus of a whitepaper on stablecoins in 2020, speculating that stablecoins might represent a “new dawn for free banking”. And of course many Bitcoiners have had a soft spot for free banking ever since Hal Finney embraced the concept as a possible means to scale bitcoin in a BitcoinTalk post in 2010. I will note that George Selgin, one of the foremost free banking economists and historians, and the man whose work Finney references in the post, generally rejects the comparison. When I asked him in 2021 what he thought of the common analogy of stablecoins with free banking (in response to an infamous paper on the topic, Taming Wildcat Stablecoins), he had the following to say:

Most of the discussion of [the failures of free banking] is irrelevant to the discussion of whether we should regulate stablecoins or not. A large part of Gorton and Zhang’s paper is written as if the debate today is a reprise of the debate in 1863 when it was “should we have a national par currency or should we stick with the state banknotes.” Today we have a national currency and the Fed. No one is talking about having stablecoins become our national currency. By most definitions, most of them aren’t money at all – that’s not what they’re trying to be. They would be a supplementary set of currency options for special uses. Treating this all (as academics do) as if we are re-debating the question of whether we should have a uniform national currency or not is ridiculous.

In this case the history is a red herring because the issues are different, the assets are different, the analogies that we have been offered are unreliable both because the old stuff has been misrepresented, and because the new stuff is much more heterogeneous than it has been presented to be. Trying to make stablecoins fit into wildcat or antebellum free banking as an analog – or money market funds for that matter – is not a good way to proceed. These things should be examined on their current merits.

But it remains the case that central bankers, academics, and politicians are tempted by the specious parallels between stablecoins and wildcat banks, as sometimes unreliable private issuers of notes into circulation. I don’t strictly blame them because the similarities are apparent on the surface level. However, in so doing, they rely on a fictionalized history of free banking, one that omits the very real success stories in Scotland and Canada, confuses the root causes for the instability of the American episode, and overstates the significance and prevalence of “wildcat” banks. Genuine laissez-faire banking is worth studying as a testament to the power of markets and incentives to create stable financial conditions with no central authority. Everyone in the crypto sector should be aware of it. And central bankers, though they may not like the implications of the historical record, have no excuse.

George Selgin, The Fable of the Cats, Alt-M (2021)

From Krozsner, Free Banking: The Scottish Experience as a Model for Emerging Economies, World Bank (1995)

By the way, all of these banks still exist today, albeit under different entities (Natwest and Lloyds

The way “true” wildcats purportedly worked (although the scale of these failures has since been disputed) was through a clever oracle attack. Rolnick and Weber summarize: “Wildcat bankers would buy state bonds that had depreciated, say, by 50 percent. They would spend, for example, $50,000 on these state bonds, deposit them at the state auditor's office, and receive $100,000 (the bonds' face value) of the new bank's currency, signed by the state auditor. As soon as the bank had its notes circulating, it would close. If the banker could get away with most of the bank's assets received in return for the notes ($100,000 worth of specie, loans, and investments), the banker would be $50,000 ahead. The bank's creditors would be left holding notes worth only half of what they paid. With easy entry and par valuation, wildcat banking could thrive, at least while the public was still unsuspecting.” Rolnick and Weber ultimately reject Rockoff’s view that such frauds were responsible for the majority of free bank failures, concluding instead more prosaically that “falling bond prices, not wildcat banking, caused most of the free bank problems in our sample states.” This latter view is the commonly accepted view today.

This definition provided in Free Banking, Wildcat Banking, and Shinplasters by Rolnick and Weber, Minneapolis Fed (1982)

I do wonder why American central bankers from the 80s and 90s were so much more precise about the true prevalence of wildcat banks. These lessons seem to have been regrettably lost to history.

Great and relevant financial history lesson.

Excellent. Thank you