AI wearables are inevitable

But are they legal?

There’s no question that millions of people will adopt AI wearables. The only real question is, which form factor will win, and who will be behind them?

The reason I am excited about these is simple. We used to have to remember the layout of cities but were then able to offload that cognitive load to google maps. Similarly, today we have to manually remember details of conversations, manually take notes, and recall them later. It’s trivial to predict that, with advances in both AI models (in terms of recognizing and summarizing speech) as well as improvements in consumer hardware, we are at an inflection point. We will soon be able to engage in cognitive outsourcing on a mass scale. With AI devices, we will be able to have perfect recall of any conversation or interaction we’ve had in the past. AI will enable us to summarize all prior interactions and semantically query this corpus as well. The cognitive load shedding will be material and a huge selling point once we collectively get over the social stigma of perpetually recording ourselves and others.

For this to work, we will need bespoke devices that collect both real-world environmental inputs (audio and video), relay this data to the cloud, and provide outputs and feedback to users. This is the AI wearable category.

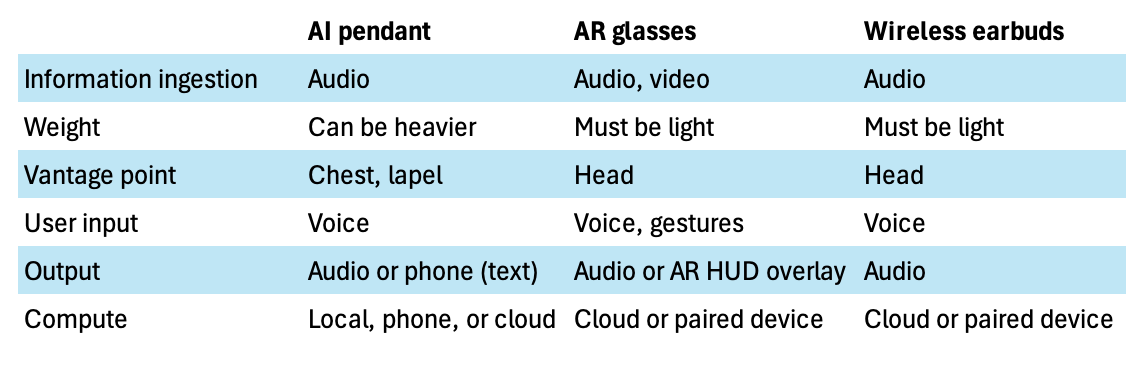

Based on my estimate, AI wearable space is currently in a form factor race between pendants, glasses, and wireless earbuds. Realistically, these will be interfaces rather than full standalone devices. The compute itself will happen on the cloud or on a paired device, with only a fraction happening “on premise”. And while some of these devices might provide direct user feedback, it’s possible that they just end up as another input to chat apps on our laptops or phones.

The pendants were some of the first movers here. You may have heard of the ill-fated Humane Pin which raised $230m and launched with absolutely terrible reviews, before selling to HP for $116m, whereupon the product was scrapped. However, there are a bunch of other names in the category, including Limitless, which raised $33m from a16z, NEA, and other top VCs. Limitless is focused on productivity and is the closest thing to “external storage for the brain” that I’ve encountered so far. Bee raised $7m and was acquired by Amazon in July. You have Avi Schiffman’s Friend (disclosure: I am a seed investor), which is positioned more as an AI companion than a productivity app.

Then you have OpenAI, which acquired Jony Ive’s io in May 2025 for $6.5b. Rumors are that they are building a screenless, pocket-sized device that will serve as an interface of sorts to an AI model running in the cloud. Little is known about the device, but it seems extremely likely OpenAI will have an offering in the pendant/pin space.

With the disclaimer that I haven’t tried all of these, none of them are really perfect. The ideal AI wearable in my view has the following characteristics:

Can passively take in and synthesize information from the world, whether it’s audio or video

Heavy enough for a charge to last all day but light enough to not bother the user

Can record audio or optionally video from an optimal vantage point (the user’s chest or head)

Ideally, can answer user queries or provide an output directly to the user via audio or video interface

Most likely, because of weight and battery constraints, the compute itself is outsourced to a GPU cloud via network connection, or locally on a paired device (phone). Only an extremely limited amount of computation would happen at the edge

Each of the emerging form factors – pendant, glasses, earbuds – explore different tradeoffs in this design space. The pendant/lapel pin can be heavier and can do more compute locally. It’s also more obvious that you’re wearing a bespoke AI device and so it might be a bit more polite, in the sense that people are being passively “warned” that they are being recorded (we will cover privacy issues later). The glasses and earbuds are more “natural” to wear and are less disruptive to incorporate, since they are established wearable categories. Glasses can also provide an alternative reality output layer, which is vastly more semantically rich than a simple audio output (like earbuds would provide) or the likely pendant output (either audio or visual on a screen). But glasses and earbuds have to be lighter, and wouldn’t have as much battery, and would be locally compute constrained.

I’ll note that I’m including wireless earbuds somewhat speculatively as an AI interface (no one really thinks of them as an AI ‘wearable’ as of right now), because the new generation of AirPods has some AI-ish features, such as the live translation. It’s easy to imagine that once Apple finally gets their act together with regards to AI, they could release a version of AirPods that collects conversational data from the environment and incorporates it into a productivity suite on the iPhone linking it to whatever AI model they choose. So for the purpose of this article, I am writing about that hypothetical future product. Some other manufacturer could beat them to the punch, of course.

Why wireless earbuds?

For people like me, I ingest a ton (90%) of work-related information through AirPods because almost all my work takes place remote on Zoom and so on. Pendants and glasses wouldn’t capture this data without some potentially complicated workarounds

It’s already totally normal to go about your day and have conversations with people with earbuds in, so no new aesthetic norm is required for them to catch on as an AI interface

It is extremely convenient to both query the AI model and receive outputs in near real time audio format. And this kind of mirrors the way we use airpods already

But at the same time, the covert nature of earbuds might actually be a hindrance to wide adoption, because a norm might develop that covertly recording people is, if not illegal, rude. If this is the case, a more explicit visual signifier that “I am recording you” might be preferred, causing people to go for a pin or pendant instead

I’m particularly excited about AI/AR glasses, especially following Meta’s recent announcement of their Ray-Ban Display, which come with a heads-up display (think Google Glass) and a wristband for control inputs. Zuckerberg clearly sees them as an AI interface, saying “Glasses are the only form factor where you can let AI see what you see, hear what you hear,” and I think they are slept on for this reason. Aside from the obvious AR use cases – directions, live captions/translations for speech, information overlays about the real world – you could also imagine these as the first step towards a Meta productivity suite which incorporates data from real-world interactions.

Why glasses?

Glasses introduce possible video and AR modalities, which makes them much more flexible than pins/pendants or earbuds (although some pins do have video capture too). Receiving information via visual cues on a HUD as with the new Meta device introduces a massive design space. Additional haptics via something like Meta’s Neural Band also adds a degree of freedom in terms of inputs, but adds complexity

The ability to capture video data and produce an output via a HUD that overlays on top of the real world means that glasses will always have an advantage over pendants or the purely audio-based AI wearables. In my opinion, AI/AR glasses are a guaranteed “winner”, but they may remain niche for below reasons

Drawbacks include the fact that some people might not want to wear (sun)glasses around all the time, and they have to be very light to be comfortable, so they will be limited in terms of battery life and the amount of processing that can be done on the device.

There’s also the “creepy factor” that might discourage some; legally, recording biometric data is questionable

And lastly you have the semi-established pendant sector, which already counts a half-dozen names.

Why pendants?

Pendants are a de novo AI consumer device, so they arguably skate around the creepy factor a bit. You aren’t surreptitiously recording people with earbuds or glasses, you have a big blinking pendant whose existence reliably tells people what’s going on

Pendants can be heavier than earbuds or glasses, so they can pack more of a punch in terms of on-premise compute and battery life

They are less annoying to wear than wearing glasses or earbuds all the time

The drawback is prompting the device and receiving output. It’s less natural to speak into a pendant and have it talk back to you. The Friend v1, for instance, still relies on the phone for a purely text output, although I expect this will change in later versions

In my view, there is absolutely no doubt that AI wearables are the next big consumer device category. In fact, I think they will be so ubiquitous in the coming years that we won’t really think of them as a separate category. It’s just that virtually everyone will rely on some sort of device that will take in stimulus from the outside world, process it with AI, and deliver insights to the wearer. Just like we don’t talk about “going online” any more – we’re just always online – we won’t really talk about “putting on an AI device”. Devices will just have AI and the ability to collect information from the outside world. But one huge question remains: is any of this even legal?

Are AI wearables legal?

Wiretap and privacy laws are one of the trickiest things about AI devices. (I’m not even going to touch on jurisdictions like Europe because I assume these things would be nuked from orbit by EU regulators.) Most states in the US are one-party consent, meaning that if you are part of a conversation, you can record it without notifying the other party. One party consent covers 38 states and around 230 million people.

However, even in one party states, “secretly” recording people that are not part of a conversation is illegal in basically every jurisdiction. Ambient (inadvertent) recording in public is a bit of an edge case and not normally sanctioned – this happens all the time when people record videos in public – but you might end up in hot water if you are storing this data indiscriminately. Most likely, the AI system would have to determine which conversations the user was party to, and filter everything else out. And this shouldn’t make the experience that much worse, since most people presumably aren’t interested in snippets of stray conversation that don’t involve the user.

In the 12 two-party states, notably including California, Florida, Maryland, and Massachusetts (110 million people in total), both parties to a conversation have to be aware that a user is recording. This places further restrictions on how AI listening devices can operate. The easiest approach is simply to have a physical on-off toggle on the device, which is only flipped on when the other party has consented. However, this relies on the AI wearable user being proactive and having the presence of mind to constantly do this, as well as asking consent, which is awkward. A smoother experience could be having the device itself listen for consent and only save the data if it hears the consent “wake phrase”, otherwise defaulting to deleting all the data. This is, as far as I can tell, exactly how Limitless’ “Consent Mode” works. This could work with geofencing for a tailored experience across state borders. (Of course, geofencing doesn’t help if we’re talking about a cross-state lines discussion. In this case, the stronger rule supersedes, so unless both parties are in a one-party consent state, you would still need to get permission.)

Additionally, wearables that are capturing biometrics will encounter further issues depending on the state. The problem is that giving people persistent identifiers is an extremely useful feature of an AI device! A general transcript of every word that has been uttered near me in a day with no indication of who said what is not really that useful. But a transcript in which specific sentences are attributed to me and to all the various people I had conversations with is incredibly valuable, especially if the AI device can build persistent conversational records with interlocutors that span multiple conversations and days. While facial recognition is generally the focus here, even a “voice print” is considered a biometric identifier in some states. Capturing biometric data like a voice print without due consent is legally risky in states like Illinois, Texas, Washington, and California. In Illinois, biometric collection requires written consent before collection. This makes the state a no-go zone for AI wearables that include this functionality.

It's kind of funny to me that our ordinary ways of interacting with people – recognizing them by face or by voice, remembering and recalling conversations, and so on – are considered perfectly normal when our brains are doing the work, but legally unacceptable when we delegate the work to an external source of compute. For this reason, I think that these regulations will soften, because they will converge to our existing moral perceptions. Once we get over the shock of outsourced brain compute being “creepy”, we will mostly acknowledge that this is just systematizing something we were all doing in the first place.

So just to summarize the legality situation:

In one-party states, recording second parties is legally fine (but incidental third-third party data would have to be discarded), although perhaps impolite

In two-party states, you would need explicit consent, but this can be achieved technologically with a “Consent Mode” and physical toggles

Voice prints and other biometric identifiers are still a third rail in some states, and I don’t see an easy way to thread this needle at present. You definitely need to uniquely identify recurrent characters in your life and attribute transcript data to them for the system to be useful. This will be a fight on a state by state basis

A secret third thing

It’s worth noting how Friend navigates these privacy issues, because I think their solution is quite unique. First, it’s worth noting that the Friend isn’t strictly premised as a productivity tool, so it doesn’t do direct recall and transcriptions of prior conversations. Instead, it is intended as a confidant of sorts you can talk to about your day and things that happen in your life.

The Friend can be manually turned on and off, but this isn’t the main way it deals with the problem. The Friend listens passively and then the data is fed into the model. The data collected by the Friend is encrypted by a key on each device, so it’s inaccessible to the developers. The voice data collected by the Friend is intended for the AI model, which is then queried by the human, rather than being fed to the user directly.

So in the case of Friend, the developers get around the wiretapping issue by encrypting the data and making it permanently tethered to the device (if you lose it, you lose your data), and by limiting the user’s ability to retrieve that data, by installing the model itself as a gate between the transcript and the output the user sees.

I don’t think this approach strictly works for productivity-minded AI devices, but I thought it was worth mentioning.

The way forward

What I think is likely to happen is that a subset of early adopters (professionals, productivity-minded people, etc) will start to use the AI wearables and eventually the social stigma will gradually abate. After all, in the business world it is already considered normal to have an AI service record and transcribe/summarize your conversations. I know a lot of people today probably think it’s inconceivable that millions of individuals will walk around with AI devices recording every word spoken to them throughout the day. In 2020 you may have thought the same about millions of people using AI chatbots as a therapist and trusted confidant. And yet it happened.

With regards to the collision between laws preventing ordinary civilians from collecting biometric data and the necessity to attribute individuals to visual or audio content collected by these devices, I think the states will eventually yield. Since AI wearables basically don’t work if you can’t connect some audio information to a person, and the market desire to have these devices exist will be overwhelming, I think state laws will eventually adapt to reflect this new reality.

great post nic